Report on International Socialists Conference 1975

| Date: | 1975 |

|---|---|

| Organisation: | Socialist Workers' Movement |

| Type: | Conference Report |

| View: | View Document |

| Discuss: | Comments on this document |

| Subjects: | International Socialists |

Please note: The Irish Left Archive is provided as a non-commercial historical resource, open to all, and has reproduced this document as an accessible digital reference. Copyright remains with its original authors. If used on other sites, we would appreciate a link back and reference to The Irish Left Archive, in addition to the original creators. For re-publication, commercial, or other uses, please contact the original owners. If documents provided to The Irish Left Archive have been created for or added to other online archives, please inform us so sources can be credited.

Commentary From The Cedar Lounge Revolution

18th March 2013

The above document is a report for the SWM internal bulletin, from an SWM guest at the IS conference. Many thanks to the person who donated this to the Archive. They offer an outline of the contents of this document below:

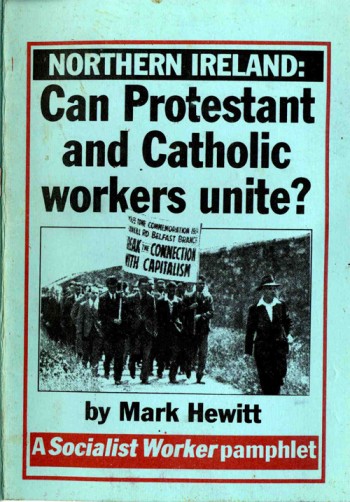

In the light of the current crisis in the British Socialist Workers Party these documents throw light on a turning point in the party’s history. The SWP’s roots lie in the division of British Trotskyism in the late 1940s. A handful of activists, grouped around a Jewish Palestinian immigrant, Yigael Gluckstein (Tony Cliff) formed the Socialist Review Group. The group were not orthodox Trotskyists and indeed were regarded as somewhat heretical because of their espousal of the theory of state capitalism regarding the USSR, their non-apocalyptic perspective (they suggested capitalism was getting stronger, not on the verge of collapse) and their dangerously libertarian, somewhat ‘Luxemburgist’ attitude towards party structure. On the far-left Cliff’s group were regarded as modest, practical and possessing a sense of humour about themselves, certainly in contrast to their rivals in British Trotskyism.

The SRG grew slowly, changing their name to the International Socialists in 1962. The IS was able to take advantage of the ferment of the Vietnam War and student protest to recruit several hundred young members by 1968. Unlike some of the other far-left groups, who were carried away by student protests or the lure of Third World guerilla struggles, the IS contended that the working class remained central to socialist strategies. They had a small core of working-class militants, some of them ex-members of the Communist Party. They embarked on a strategy of focusing on workplace sales of their paper, Socialist Worker, and of building rank and file groups among union activists. As working class militancy escalated in the early 1970s the IS was able to grow modestly among manual workers, recruiting miners, steel workers, in the car industry and transport. (Three respected London dock shop stewards, Eddie Prevost, Bob Light and Mickey Fenn, all former CP members, joined IS during this period for example.) Rank and file groups were set up for teachers, nurses and local government workers as well as in the factories. At one point the organisation even set up factory branches. (The best history of the organisation in those years is Jim Higgin’s memoir More Years For the Locust ).

As Higgins notes:

‘The Bellevue Socialist Worker Rally, in Nov 1973, was successful with 1,200 people attending. The following April, the Rank and File Conference was held in the Digbeth Hall, Birmingham. Some 600 trade unionists applied for credentials and it is possible to gauge the effectiveness of the previous work with rank and file papers by the fact that of 32 TGWU branches participating eight of them were from London bus garages where Platform circulated. Hospital Worker encouraged nine NUPE branches, two T&G and one COHSE branch to send delegates. Carworker was influential in getting 21 AUEW and TGWU branches in the motor industry and 27 shop stewards’ committees to the conference. In all more than 300 trade union bodies applied for credentials, including 249 trade union branches, 40 combine and shop stewards’ committees, 19 trades councils together with a few strike committees and occupations. If this did not look like the Petrograd Soviet in 1917, or 1905 come to that, it was a very creditable event. It is true that a majority of the contributions from the floor were from IS members; it was still a matter of consequence that they were all experienced trade unionists with something credible and apposite to say. Better still was the fact that there was a not insignificant number of non-IS militants who spoke in support of the programme and in favour of a continuing organisation to develop the rank and file movement. Outstanding among these was George Anderson, chairman of the joint shop stewards’ committee at Coventry Radiators, and Joe McGough, convenor of Dunlop Speke and chairman of the Dunlop National Combine Committee.’

Higgins argues that the IS in the mid-1970s missed ‘the very best chance we have had since the 1920s to build a serious revolutionary socialist organisation.’ As the documents reproduced here reflect, the prospect of revolution in Portugal had also raised hopes of radical change. But within the IS the problems of maintaining a workplace focus were becoming apparent. (Note too the role members played in trying to dampen anti-Irish feeling in the car factories in Birmingham after the November 1974 bombings).

The IS would see several small splits over the next few years, many of them raising questions about the leadership’s commitment to internal democracy, and in 1977, at the urging of Cliff and his supporters, would transform itself into the SWP, an avowedly ‘Leninist’ party. (Cliff’s three volume biography of Lenin has been unkindly described as being like a biography of John the Baptist by Christ himself). The turn to the SWP was accompanied by another round of splinters.

The effect of these was not readily apparent because the party’s central role in anti-fascist struggles and in unemployment agitation meant that it continued to recruit young workers into the late 1970s. By the 1980s this had changed however. The advent of Thatcher and Reagan saw the party adopt the perspective of the ‘Downturn’: the workers movement was on the defensive internationally and therefore a rank and file perspective was unrealistic. Instead the party concentrated again on student recruitment which meant that by the mid-1980s, while claiming a membership of 4,000, the SWP was heavily white-collar and student based. A small number of manual workers remained but for a variety of reasons the period of the early 1970s marked their only serious toehold in the broader working class. The party however maintained a full time apparatus, a weekly paper and a presence that could sustain itself through the next two decades. As a member in the 1980s, the early 70s were always held up as an example of how the party could grow in a period of workers struggle. Why a large chunk of that membership and influence were lost was never adequately explained. It is unlikely that the party will ever get an opportunity like that again. Current events suggest that they would not deserve it.

By More in sadness than in anger.

More from Socialist Workers' Movement

Socialist Workers' Movement in the archive

Comments

No Comments yet.

Add a Comment

Comments can be formatted in Markdown format . Use the toolbar to apply the correct syntax to your comment. The basic formats are:

**Bold text**

Bold text

_Italic text_

Italic text

[A link](http://www.example.com)

A link

You can join this discussion on The Cedar Lounge Revolution

By: BB Tue, 19 Mar 2013 17:00:07

“… The reaction of the Irish left to Labour in 1970 was not unique. Internationally, events in the 1960s had pushed reformist political organisations leftwards and centrist currents had generally formed uncritical political blocs with left labour leaders and social democratic parties set in after the upheavals of 1968-71 right across Europe. Now reformist parties were execrated by the centrist groups, some of whom had even been ‘deep entrists’ in reformist parties. Believing reformism to be irrelevant many now counterposed directly the building of the ‘revolutionary party’.

SWM reflected this swing to a one-sided rejection of Labour. The 1973 election merited a huge headline in the election issue – ‘No Choice, No Change’, but only a few paragraphs of comment, and no call for even critical support for Labour against the openly capitalist parties. The Labour Party merited only a passing mention as a party of treachery. But SWM was prepared to call for votes for other ‘lefts’ is they should stand. Labour’s pro-Coalition politics was decisive for SWM; its significance as a focus for workers was ignored.

A decade later, following the reconsiderations by Cliff in Britain and other centrist tendencies internationally, SWM would find it possible once more to call for critical support for Labour. Throughout all these twists and turns, however, the method used to decide the position in 1973 would remain the same for future elections – tailing whatever looked ‘left’ at the time, but failing to recognise or confront the illusions of the most active workers in reformism.”

Extract: The Socialist Workers Movement: A Trotskyist Analysis, p.8 (A Class Struggle Special by the Irish Workers Group, in 1992)

Reply on the CLR

By: Branno's ultra-left t-shirt Tue, 19 Mar 2013 17:22:50

SWM called for a vote for Official Sinn Fein in the 1973 general election

Reply on the CLR

By: WorldbyStorm Tue, 19 Mar 2013 17:36:08

In reply to Mark P.

Yep, the electoral turn was certainly a change.

Reply on the CLR

By: Mark P Tue, 19 Mar 2013 21:31:45

In reply to WorldbyStorm.

Yes, although to be fair, officially the issue of standing in elections was always considered a tactical question rather than something they were against in principle. They sometimes gave the impression, in their cruder moments, that it was a principle but in theory they were always open to a turn if the time was right.

Reply on the CLR

By: Branno's ultra-left t-shirt Wed, 20 Mar 2013 21:02:50

It never ends…

Reply on the CLR

By: Branno's ultra-left t-shirt Fri, 22 Mar 2013 07:55:02

Fairly poor attempt at explanation here

http://www.guardian.co.uk/commentisfree/2013/mar/21/challenging-sexism-heart-swp-work

Reply on the CLR

By: Branno's ultra-left t-shirt Fri, 22 Mar 2013 07:55:47

Which is a reply to this

http://www.guardian.co.uk/commentisfree/2013/mar/12/swp-rape-implosion-why-i-care?INTCMP=SRCH

Reply on the CLR